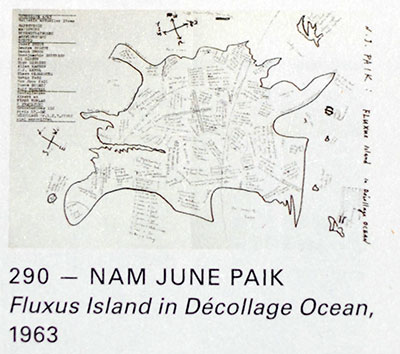

Fluxus Island

The island that isn’t there

Gianni Emilio Simonetti

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers!

“Alongside decayed roués with dubious means of subsistence and of dubious origin, alongside ruined and adventurous offshoots of the bourgeoisie, were vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, scoundrels, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, pimps, brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ grinders, rag-pickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars—in short, the whole indefinite, disintegrated mass, thrown hither and thither, which the French call la bohème”

Karl Marx

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, 1852

“1962 Wiesbaden-1978 Boston. More than one winter has gone past in this intermezzo in which the glaciation of meanings in the Western arts has given way to the orgiastic fermentation of signs and merchandise.”

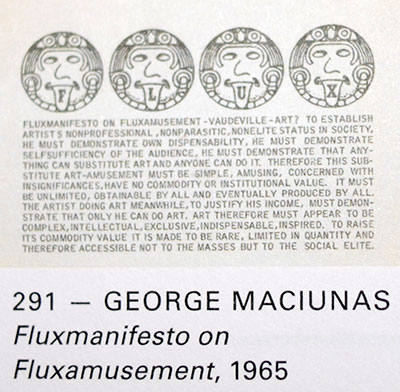

—George Maciunas

When George Maciunas set sail for the archipelago of the Virgin Islands it seemed clear that Fluxus—at this point— had derived from the geography of an idle art the task of mending the fracture between the configuration of the event and the world. So why was there a shipwreck? Because events can’t be fabricated, just by wishful thinking. On these islands, for example, it is believed that ginger protects against seasickness.

As for the idleness of art, it should not be assimilated to anti-functionality so as not to obscure the part of it which leads to the irreducible element that governs it: nothing (Kazimir Malevich).

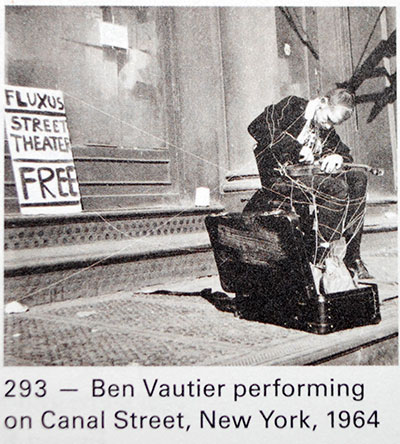

“L’art, c’est un mot.” —Ben Vautier

In the etymology of the Italian word for shipwreck, naufragio, there is a fissuring: one is never shipwrecked twice off the same beach. The reason is tautological. This fissuring in the imagination represents a paradigm of the semiotic view, an interval between the foaming billows of an island that has never known the happy few.

In the prescription of the event, reiteration can be assimilated to a semiotic impression, that is to say an impression of installation that gets the upper hand over the oral character of the rêverie that turns into work. In this event gender—which is what makes the distinction in the museums and arouses the anger of the Guerrilla Girl—is what psycho-analysis defines as a more-than-anything-else imprisoned by the male and conquered by carnival. As Joyce Mansour has stressed in other circumstances, it is hard to wear otherness if one has a vest made of breasts, whence the policy of cross-dressing ushered in by George Maciunas and still not understood.

Isn’t it curious that in Athens milk has been one of the social forms of the polis?

Arthur C. Danto, who likes what used to be taught in schools as domestic science, notes a dietary (feminine?) origin in the history of Fluxus, which is counterbalanced by Jackson Pollock’s way of urinating, inherited from his father and “of great hermeneutical importance” … “to understanding the technique of dripping.”

“Fluxus is the only artistic movement capable of eating its own tail.” —Ben Vautier

In the event, after the computer chill, the object has not rediscovered its innocence, but the reasons for its metamorphosis. Reasons that challenge the principle of reality and present it as a social relationship between individuals.

As a singular thing that condenses an excess of meaning and appears as a symptomatic hybrid of signification. In other words, in Fluxus the event is in re and not ante rem.

Hunters say that the nightingale is a peculiar bird. When you hear it sing, you don’t see it—when you see it, it doesn’t sing. Could this be why empiricism in the arts is never entrusted to a correspondence between the senses?

Yes, if we pay heed to Etienne de Condillac.

Finding the object in the world seemed to Maciunas— in the years of his poetic exile in Europe—to be a transformation of the world, notwithstanding the predominance of Pop Art and its infatuation with the brand and the packaging that does not alter just the value, but the meaning too. Whence—among other things—its commercial success: that of investment in the process of social standardization (Georg Simmel).

Let’s say that Fluxus has never possessed the referential vision of the art of its time.

“Art is what makes life more interesting than art.” Robert Filliou

There is in the Fluxus event an apparent constant that renders apparent its constants as event. As a result of which the law that governs the flow of banality takes on a narratological form. Put another way, language in Fluxus would have liked to be that return of feeling which lies in the aesthetic experience like water in water, so that all hermeneutics is superfluous. On the contrary, warns George Bataille, language is unavoidably subject to the giddiness of being.

“Fluxus is the unconscious of the unconscious.” C.Dreyfus

The Umwelt of the arts is semiotic. For this reason the event, in spite of itself, is a bearer of meanings that are peculiar to it. In this key Fluxus still looks like an effect of speech, in which the event competes with its inhabiting in order to interpret its destiny (Geschick), definable as a con.figuring, although only as long as it makes the figuration coexist with its other etymological theme, that of make-believe. All this while the imposition of a division emerged, the one between hyle and morphe that conceptual theses anchor to the metaphysics of techne.

Hyle and not matter, so that the maternal may take its course.

At this point of the dis.course, what is a Fluxus event? It is a mowing of the grass in Herr Heidegger’s Lichtung in the vicinity of Todtnauberg, in the Black Forest. Is it not said that being, but not beings, stands out as if in a clearing? The derisory acuteness of Fluxus lies in keeping the clearing cleared. If we were Barbara Kruger we would say that otherwise grass would start to grow behind the representation.

Nevertheless there is no doing in Fluxus. Rather there is a stemming of the aporia to which the processes of commercial exploitation inevitably lead it.

“Art’s obscured the difference between art and life. Now let life obscure the difference between life and art.” —John Cage

In the face of the compulsive repetition and the trauma of the self and in the distinction between Wiederholen and Reproduzieren (the reference is to Hal Foster who cites Jacques Lacan and the darkness in which reality is cloaked),

Fluxus has worked the magic of producing indecision, of favoring the realism of the discard, shunning the decomposition of the whole. An effective remedy for the disasters of Saturday night and the nostalgie du dimanche, a drop missing from the sea.

Here, if we define the real as a material, the realism of the object is the new naturalism of the arts, ushered in originally by Duchamp and Man Ray’s Elevage du poussière.

“Fluxus is almost nothing.” —Joe Jones

The event, understood as a set of events, shows how Fluxus, in itself, represents the sense of that con.fusion from which derives a characteristic of its poetics in the form of a globalism of sensation. Sensation that we could define as a con.figuration in opposition to a purely additive—aesthetic— totality of associations. In the Critique of Pure Reason Emmanuel Kant’s pedantry led him to write: “Totality”—as event—“is nothing else but plurality contemplated as unity.”

Thus Fluxus appears as an awareness of the remnant (André de Murait), the path of recirculation back to Howth Castle.

“I don’t believe there is a difference between theater and any other act that I perform.” —Bertolt Brecht

In his autobiographic Stéphane Mallarmé observed that works sparkle when with the whole ils font le reste, sacrificing it (this tout) to repetition, as we will see in the following century with Andy Warhol, who turned it into an et cetera of representation. In a compulsiveness that wanted to arrest the corrosion of time. Rather than another figure of performance, however, this is a giving in that does not know les figures de l’inachevé.

Just as irrational numbers scandalized the Greeks, Fluxus has scandalized its time, presenting an irreducible remnant that undermines the sum of value and what the “conceptuals” define as a principle of molding. This remnant, in Maciunas’s poetics, has always been a sample taken from the nothing, of which we find the icon in the indefiniteness that narrates it. This indefiniteness is similar to George Bataille’s “unknowing” or, in philosophy, the almost nothing with which Vladimir Jankélévitch sanctions meaning, for some time now become an échec de la totalisation in the arts.

Kant again: “the indeterminate contains the fundamentals of the part.” In the enclosure of the event these fundamentals are the “compartments” in which its enigma is in.stalled. Far from solving it, the task consists in presenting it to the observer (Heidegger).

Intermezzo. What is a remnant?

“Madame?” I said, “I must play now because…” As I had forgotten the reason I abruptly sat down at the piano. And then I remembered again. The pianist stood up and stepped tactfully over the bench, for I was blocking his way. “Please turn out the light, I can only play in the dark,” I straightened myself.

At that moment two gentlemen seized the bench and, whistling a song and rocking me to and fro, carried me far away from the piano to the dining table.

Everyone watched with approval and the girl said:

“You see, Madame, he played quite well I knew he would. And you were so worried. ”

Franz Kafka, Description of a Struggle. (Our italics.)

“Fluxus is a bunch of spoiled brats.” —Nam June Paik

Appendix. The preliminary materialist question in the arts, in memory of G.M. (12 symptoms).

First. Art is not a thing, it is a cause. Just like hysteria is a corporal prodigy.

Second. The materialistic argument, which occupies a position between corporality and sociality, constitutes the functional link between the senses and sense, between representation and meaning. In the same movement it dissociates the supposed one between body and mind, between nature and culture.

Third. The “vegetation of objects” is the new still life of modern art. It suffocates the substance of the thing.

Fourth. Linguistic excess leads the visual to blindness and, further on, to the revulsions of abstraction. In so doing it demonstrates the opacity and heaviness of the spirit that has long forgotten the nobility of the wind that turned into pneuma.

Fifth. Martin Heidegger writes, the young girl who is engaged in a task too difficult for her can be said to be a young thing, still too young for it (ein noch zu junges Ding).

How to put it? Uma coisa ainda muito nova… a little thing, that behind the green door of desire becomes the origin of the world, even in spite of Gustave Courbet’s anatomical realism.

Sixth. The being other of the res (Ding) is the form of merchandise, its “usability” is united with its Gestalt.

A condition that makes ability an attrition.

Seventh. If the edifice of the representation “con.forms” the “significance” is a hotchpotch of liver and black figs.

Eighth. When the chips are down, for idealisms meaning is always transcendental, and so it is in the form of a

distraction.

Ninth. For the work of art historicity is an infinite alteration of the style on which meaning contorts the form even where the significanza makes it flat.

Tenth. Representation is the bad substance of meaning. A substance that embraces the reality that it does not re.cognize and the imaginary of which it fears the symbolic rains. This is why in the complex emblem of the Borromeo family the rings go rusty and it grows dark on the trou around which the psychosis is organized.

Eleventh. Representation is a denegation of the void. Different are the lost trace and resemblance. Different is the remnant as testimony of what does not fade.

Twelfth. Eating sugared icons in the museums. There is always a plus-enjoyment that glimmers behind the mutilations inflicted by bites. In the shadow of the counter-reformations.

“Demolish serious culture.” —Henry Flynt

“Und jede nimmt und gibt zugleich / und strömt und ruht.” — C.F. Meyer

ADDENDA

Judge: “If you saw it in the forest you would not take a shot at it?

Edward Steichen: “No, your honor!”

Can we tell the little story of the Fluxus adventure, reflecting on its significance for ourserlves?

In 1928 one of Constantin Brancusi’s oiseaux, disembarking from the steamer Paris, ran the risk of losing its feathers at the New York customs: see Brancusi contre États-Unis. Un procès historique, Paris 2003. About thirty years later Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes went back to being what they were—boxes of soap pads for cleaning dishes—when passing through the Canadian customs.

As Friedrich Hegel had pointed out in his day, it is hard to go along with suitability, especially, we might add, when it is the product of an asymmetry.

Between these two anecdotes art criticism has done more, it has learned to struggle on: it has invented the categorical proximity between object and work. In this way a urinal has earned—to the sniggers of a Swiss linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure—a name in italics and the title of fountain in the books.

The story takes us back to 1913. In the meanwhile, the artist Marcel Duchamp changed gender, became librarian at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris, read Henry Poincaré and discovered the power of science to lay bare what matters in reality: the relationship between things.

If there is a point of contact with Maciunas it is all here, but it turns out to be in a narratological key.

Things in Fluxus have ended up in the box, sterilized by commercial infection and as dangerous as kryptonite, an imaginary substance that destroys processes of exploitation.

We take a step forward by flying. In more or less the same period Duchamp had met Brancusi at an exhibition of aeronautical technology and had declared his admiration for the beauty of propellers. For those familiar with the Romanian’s birds the rest is consequence.

Note. In this paragraph it is the italics that make the work. They turn a city into a steamer. A bronze spear into a work of art.

Can mémoire involontaire correct the course for Utopia? If we are on the quarterdeck reading Baudelaire do we still look like survivors from a wreck?

Meanings are always symptomatic. In the face of the fissures in history the theatrical minimalism of Fluxus can be seen for what it is beyond the principle of coherence. It is no accident that the metamorphosis of poiesis in the form of a Fluxus event is condensed in Freud’s formula Fort/Da.

“At first glance it looks like a flat star-shaped spool tor thread» and indeed it does seem to have thread wound upon it; to be sure, they are only old, broken-off bits of thread, knotted and tangled together, of the most varied sorts and colors. There have been moments in the history of Fluxus in which Maciunas has also been a family man. Odradek.

Last century, when I was twenty years old, the orphans of Aden Arabia, like the author, had to cope with a “retinal” art made up ot lumps, stains, drippings, tears, gestures and geometries. Having completed my sentimental education in the pages of the Bibliothèque International d’Érotologie published by Pauvert, I felt the Darmstadt of the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik to be closer. As if to say, another island, another utopia. I started to write “mute-music”—

Mutica—an alliance of imperatives and dérives, of words and silences.

As a jeune fille I was noticed by John Cage, ending up in the pages of Notation. Then came George Maciunas, the année terrible and “the turning of the arts into a social and historical object”—this is not a concept of Lukàcsian realism, but a statement by Arthur C. Danto for whom—along the lines of a masked ball—a context is enough to make a work.

“Everything is art, everything is politics.”

—Joseph Beuys

When Fluxus was mistaken for a dépendance of the USPS it really constituted a disturbing element of artistic value, capable of making people aware of the possibility of regaining possession of everyday life by producing social ties.

In others words competence seemed to me like the ability to translate into a sensitive language what my Parisian friends of the Marais called des questionnements, des prises deposition critiques. The boxes from this perspective were intended, like the Fluxconcerts, to be wedges positioned to derail the destiny of art, caught between a past that had defined it as a dépense improductive, and a future in the society of spectacle as loisir de masse.

The autobiography needs another note. There was in the Maciunas system an “anthropological” apprehension about artistic activity that made the event a “social” question, just as there was something of dada anarchy in the form of the event. I wasn’t thirty yet, and it is not hard to imagine my enthusiasm when Fluxus was accused of having slipped a goldfish into the holy-water stoup of Notre Dame in Paris.

“Le spectateur fait l’oeuvre.” —Marcel Duchamp

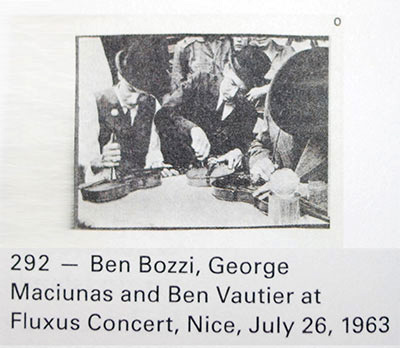

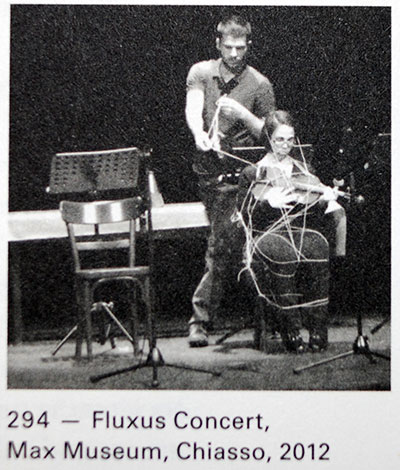

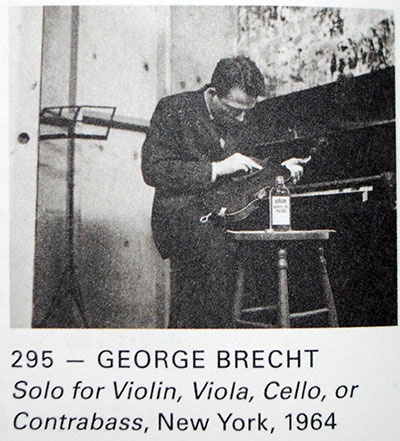

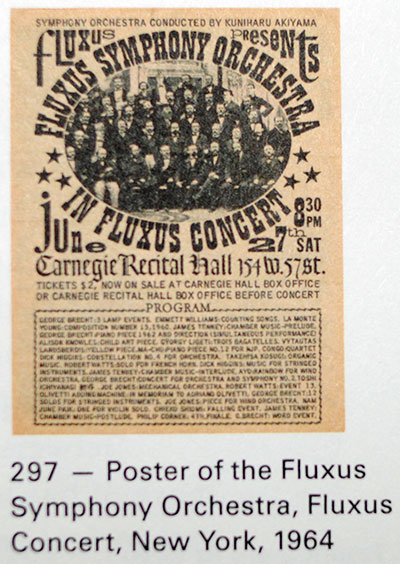

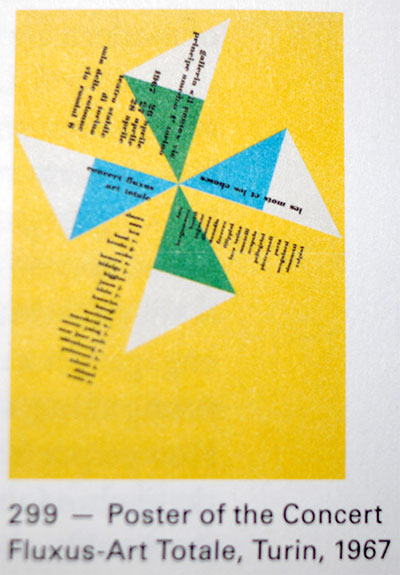

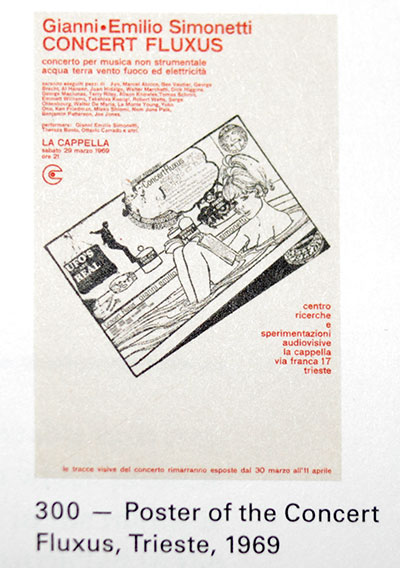

The first Fluxconcerts in Italy: 1964—Gesto e Segno, Milan. 1966—Concerto Fluxus per aquiloni, Campo Imperatore, Terminillo, Rieti. 1967—Concerto Fluxus, Teatro della Piccola Commenda, Milan. Flux.concert, Librería Rinascita, Milan. “Les mots et les choses.” Concerto Fluxus, Teatro Gobetti, Turin. Flux.concert, Teatro Dionisio, Rome. Concerto Fluxus, Galleria La Bertesca, Genoa. Flux.event, Villa Cuccirelli, Gallarate La Bertesca, Genoa.